A generation of the musical public grew up and had its taste shaped under the influence of Beniamino Gigli’s recordings; and among them a generation of young tenors blossomed under this same influence into artistic maturity. Undoubtedly the great Italian tenor was one of the most influential singers of the entire period that followed World War I. Gigli’s style of singing – on stage and on disc – has been the subject of much criticism and controversy.

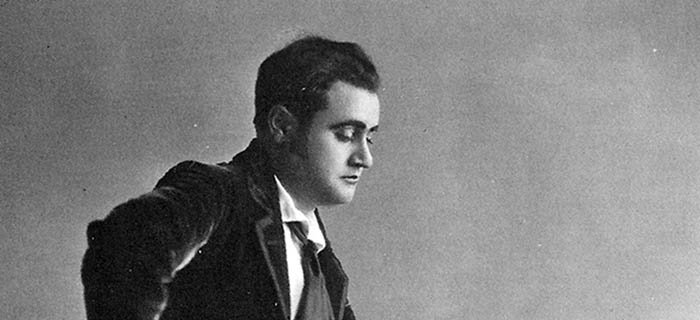

Late on the evening of 14 May 1918, after a performance of his Lodoletta at the Teatro Lirico in Milan, Pietro Mascagni introduced two men to his young star tenor, Beniamino Gigli, who were to have a profound influence on his future life and career. One was Fred Gaisberg, noted American-born sound engineer of His Master’s Voice in London, who had been the first to record Caruso, Melba, Patti, and Olimpia Boronat; the other was Carlo Sabajno, an Italian conductor who was Artistic Director of La Voce del Padrone, the HMV subsidiary in Italy, and was to devote his life to recorded music. Both men had witnessed Gigli’s first Milan triumph that evening in the role of Flammen, had been deeply and abidingly impressed by him, and were eager to enter into a recording contract with him for their organization, the more so because they knew that their rival, Columbia, was already negotiating for one. They moved quickly. On his first free day, 17 May, they made a test recording of Gigli’s voice, and that night Fred Gaisberg wrote to his brother, Will Gaisberg in London, who was also an operative of HMVs, urging him to ensure that a contract with Gigli be concluded expeditiously. He would have a great career, he said, likening him to Caruso, although with a more flexible and lyrically ringing voice.1 The result was indeed an early contract, and in October and November 1918 Gigli made his first recordings for His Master’s Voice, transferring to Victor for ten years in 1920.

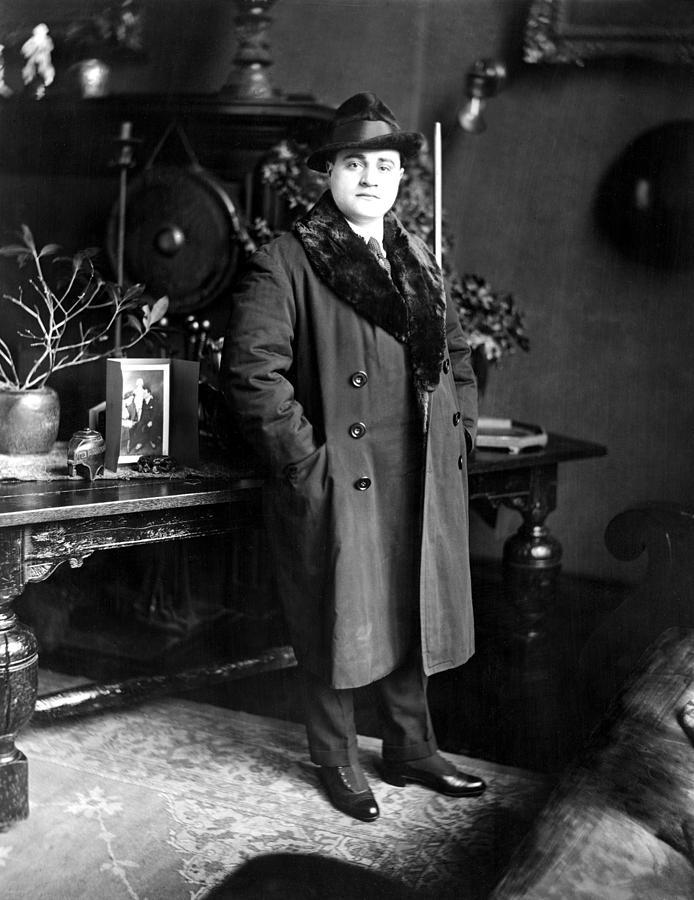

Gaisberg and Sabajno were not mistaken in the high hopes they held for their new tenor discovery, for within less than a decade Gigli had emerged as the master tenor of the whole period of the electric 78rpm disc. All his records sold well; many were runaway best-sellers which, although they were released on the expensive Red Seal label, vied with more transient popular hits in the sales they achieved. Victor and HMV, the very companies that recorded most of Gigli’s more famous tenor colleagues, minced no words about him. During the acoustic recording period, Victor described him on its record covers as “Caruso’s Successor at the Metropolitan Opera;” during the electric recording era HMV described him on its covers as “the world’s greatest tenor”. Consistently Gigli’s recordings received glowing reviews. In The Gramophone,Herman Klein wrote of them in the most appreciative terms, sometimes expressing preference for them over their acoustic Caruso redecessors, commending Gigli’s singular interpretative gifts, and calling his 1931 recording of “Che gelida manina” from La Bohème “indisputably flawless”.2 Comptom MacKenzie, the founder of The Gramophone,expressed the opinion that Gigli’s 1933 recording of “Una furtiva lagrima” from L’Elisir d’Amore was the most beautiful vocal recording he had ever heard.3

This was high praise, but it was fully in accord with almost unanimous world opinion at the time. Famous composers such as Puccini, Mascagni, Giordano, Cilèa, and Montemezzi held Gigli in the highest esteem and implored him to sing their works. Great tenors such as Alessandro Bonci and Giulio Crimi spoke or wrote of him in the most flattering terms.4 Giovanni Martinelli held him in awe and listened to him in wonder.5Others such as Giacomo Lauri-Volpi and John McCormack were filled with life-long envy of him. Gigli’s celebrated colleagues, Feodor Chaliapin, Amelita Galli-Curci, Toti dal Monte, Rosa Ponselle, Claudia Muzio, Maria Caniglia, Sara Scuderi, Mafalda Fàvero, Gianna Pederzini, Giuseppe de Luca, Tito Gobbi, Paolo Silveri, and many others, shared these views.6 The critics of three, and eventually four, continents concurred. Prominent among them were such outstanding figures as Giovanni Bellezza in Naples, Adriano Belli in Rome, Rudolf Kastner in Berlin, and W. J. Henderson, Richard Aldrich, Olin Downes, Pitts Sanborn, Pierre Key, Leonard Liebling, and Salvatore Fucito, Caruso’s former accompanist, in New York. Henderson even described a performance of Massenet’s Manon at the Metropolitan on 7 December 1931 with Gigli and Lucrezia Bori as the finest performance of opera he had ever seen, and his recollections reached back beyond Caruso and Bonci to Jean de Reszke.7

A generation of the musical public grew up and had its taste shaped under the influence of Gigli’s recordings, which most of them saw as the acme of vocal art in the tenor voice; and among them a generation of young tenors blossomed under this same influence into artistic maturity. Ferruccio Tagliavini paid Gigli the tribute of direct, albeit distinguished, imitation. Innumerable other tenors disclose his influence either in their singing or their interpretations. To the young Jussi Björling, Gigli was his favorite tenor, as he was too to his wife Anna-Lisa.8 Undoubtedly Gigli was the most influential tenor of the entire period that followed World War I.

Such weight of opinion did not seem to be reversible, and in a sense it never was quite successfully reversed. But as the turbulence of the Great Depression led into the still greater turbulence of World War II, with political, national, and racial attitudes intruding on the world of music, a revisionist body of criticism began to emerge, first in Britain, then in the United States, and finally even in some quarters in Italy. According to this view, which paid scant regard to the weighty opinions that had been so extensively expressed in earlier years, Gigli was stylistically flawed. In what developed into little less than a litany of artistic hatred directed against him, it was alleged that he marred his vocal line with aspirates, that he was excessively and inexcusably lachrymose, that he had developed mannerisms in the course of frequent performance, was often unfaithful to the score, was essentially a lyric tenor whose voice was unsuited to more dramatic works, that he indulged in falsetto, and, in one of the more stunning contradictions of critical comment, that he held his high notes too long while simultaneously having a deficient top. In certain modernistic quarters in Italy, eager to discard the heritage of the Italian past in order to venture into some brave new world of the aesthetics of the ugly and the nondescript, even the admitted beauty of Gigli’s vocal tone was denounced as self-indulgent musical hedonism.

Such weight of opinion did not seem to be reversible, and in a sense it never was quite successfully reversed. But as the turbulence of the Great Depression led into the still greater turbulence of World War II, with political, national, and racial attitudes intruding on the world of music, a revisionist body of criticism began to emerge, first in Britain, then in the United States, and finally even in some quarters in Italy. According to this view, which paid scant regard to the weighty opinions that had been so extensively expressed in earlier years, Gigli was stylistically flawed. In what developed into little less than a litany of artistic hatred directed against him, it was alleged that he marred his vocal line with aspirates, that he was excessively and inexcusably lachrymose, that he had developed mannerisms in the course of frequent performance, was often unfaithful to the score, was essentially a lyric tenor whose voice was unsuited to more dramatic works, that he indulged in falsetto, and, in one of the more stunning contradictions of critical comment, that he held his high notes too long while simultaneously having a deficient top. In certain modernistic quarters in Italy, eager to discard the heritage of the Italian past in order to venture into some brave new world of the aesthetics of the ugly and the nondescript, even the admitted beauty of Gigli’s vocal tone was denounced as self-indulgent musical hedonism.

According to these lines of comment, Gigli might have been popular, he might have been prominent, highly successful and highly paid, his records might have sold in millions, he might have had the gift of raising the multitudes, but he was flawed as an artist and people of refined taste should prefer the more restrained singing of some far less noted English, Scottish, Irish, American, Danish, or German tenor, one of true musicianship whose singing was marked by restraint and that most elusive of qualities, “a true sense of style”.

Much of this criticism was demonstrably false in fact and unfounded in theory; the writers concerned did not even refrain from misrepresenting what earlier critics had written. But a great deal of fine Italian and Spanish singing became mired in the process of the denigration of Gigli, for these singers, too, were seen as sharing some of his imaginary flaws. The damage done to the art of singing, and also to the art of listening, by the repeated bombardments of much of this writing cannot be calculated but must have been considerable, for a whole generation was advised not to believe its ears, and was admonished if it did. The bitter fruits of this can be seen in the present crisis in singing, which threatens to bring down the entire edifice of world opera as it has been known.

Subsequently, another tone emerged in most comment on Gigli and his recordings. In this he is seen once more as the great tenor he was, indeed as the greatest of all the post-Caruso tenors and as one of the greatest singers in all history, the possessor of what may have been the most beautiful tenor voice ever heard. But he is also often said to remain artistically flawed in spite of this. The Rome Opera House may name the piazza that fronts it after him in a unique tribute, his bust may grace its foyer while others reside in the Metropolitan and the Scala, more than forty thousand of the forty-three thousand reviews that are preserved today in the Museo Gigli in Recanati may praise his singing with eloquent liberality, and his recordings may still sell profusely in multiple editions on CD, but he remains to some extent flawed because these critics have said so, and others have hesitated to contradict them.

Style, as the word is used in these writings, becomes a word shorn of most of its meaning, little more than a synonym for restraint, conformity, and lack of

originality, whereas it should signify the individual imprint of the artist on the work while achieving maximum of effect with minimum of effort. Good taste, Giulio Gatti-Casazza once remarked, is simply the result of continually hearing the best over a long period, and that is exactly what the English originators of this line of comment on Gigli did not have an opportunity to do, since the best international opera was performed only occasionally and briefly in the London of their time. What distinguished them was not their taste, but their pretentiousness and their provincial pedantry. What is still more remarkable about their writings is the absence of any inquiry into the aesthetic world Gigli represented and of which he was a reflection, into the values that played upon and molded him, or the art, music, and conception of opera to which his singing was a response.

In another passage, Gatti-Casazza wrote that style and technique count for nothing in opera; what does count, he said, is genius9 — and Gigli possessed a genius for singing that his whole life reflected and that is undeniably unsurpassed. It is this that the Gigli denigrators have entirely overlooked, and when genius is removed from opera or from any other field of aesthetics, we are left with mediocrity, the ultimately futile artifices of publicity, and the present crisis in singing. Genius, moreover, sets its own rules.

When today we begin to listen to Gigli’s recordings in chronological sequence, the voice at once lays a spell on us. The mundane world of outer reality that surrounds us is dissolved and we enter a domain that we realize has always been within us. Our eyes open, new horizons appear, and the spell gradually deepens at both conscious and unconscious levels. The voice we hear is one of unexampled beauty, pure and round in tone, luminous on every note, mellow and vibrant, sweet and beguiling to the ear, and it is suffused with a softness, the prized morbidezza of the Italian school, that extends even to its forte and fortissimo passages. There are no register breaks, no impediment to the absolute homogeneity of the voice over a scale of two octaves. The high, the middle, and the low notes are all equally well sung. The voice is uniquely liquid; it flows over the music with the uninhibited naturalness of speech. It is untouched by any suggestion of hedonism, of sensuous beauty enjoyed for its own sake, because it has to it, even in its most joyous and sparkling moments, an underlay of melancholy that speaks to us of many things that are remote from transient sensual delight. It becomes a mirror of all that is within us, of the joys, sorrows, passions, yearnings, anguish, ardor, and sadness that, between them, comprise the totality of subjective human experience; and the beauty of the voice is indispensable to the spell it lays.

As an artist, Gigli was a product of the highly cultivated world of music, art, poetry, and pageantry that was Rome in the decade before World War I. As a child he

lived and sang in an Italian cathedral, displaying a gift for singing that amounted to genius from an early age. He was reared on the music of Lorenzo Perosi, Gounod and Bizet, and the poetry of Giacomo Leopardi. Hundreds of Masses filled out his early repertoire. As a young man, he studied, knew, and mixed with famous musicians, composers, teachers, and singers. Among them were Pietro Mascagni, Umberto Giordano, Alfredo Martino, Francesco Marconi, Antonio Cotogni, and Enrico Rosati. At the opera he drank in the art of the greatest singers, Celestina Boninsegna, Rosina Storchio, Gilda dalla Rizza, Mattia Battistini, Giuseppe de Luca, and the tenors Alessandro Bonci, Hipólito Lázaro, Bernardo de Muro, and Tito Schipa. From Antonio Cotogni, his first teacher at the Liceo Musicale di Santa Cecilia and Italy’s greatest baritone of the nineteenth century, a singer who had sung with Adelina Patti, Nellie Melba, Angelo Masini, and Julián Gayarre, and taught Jean de Reszke as a tenor, he acquired an unshakable taste for that element of operatic grandeur that had distinguished the Italian lyric stage in the nineteenth century. With his second teacher, Enrico Rossati, he developed a view of singing as an art that saw it not as the molding of a voice and style into the forms of some predetermined classic ideal, but as the progressive unfolding of the propensities of voice, personality, and expression that were the peculiar gifts of the individual artist. “There must be no slavish imitation of anybody at any time,” Gigli said later.

This was not a formula for unlimited license. Gigli’s whole training had made him very much an artist of the toute ensemble, faithful to the score and to the living realization of the composer’s intentions. His recordings, closely listened to with the relevant scores in hand, confirm this, with the exception of a few virtuoso touches that are not unworthy of a great tenor for whom there existed ample precedents. His recordings also disclose that he was an excellent ensemble singer, able and willing to modulate his tones to blend with those of his colleagues while still rising above theensemble when the music requires the effect.

Fundamental to Gigli’s conception of opera was the conviction that drama is its essence. Not, it should be said, the drama of the harsh and indifferent external world of facts and objects or of the naturalistic stage, but the drama of the interior world, of all those feelings, sentiments, passions, emotions, and even illusions, that comprise our consciousness of life, which poetry, when it is raised to the estate of music, as it is in opera, is so well adapted to portray. Hence the equal stress Gigli places on his beautifully enunciated Italian and the shadings, inflexions, stresses, mezzo tints, and climaxes of his singing.

But drama, especially the drama of the interior life, has its own prerequisites and terms; and feeling, nuance, passion, and emotion are very much germane to them, just as undue restraint or what has been tendentiously called “a proper sense of style” may be inimical to them. The tears of Gigli’s singing can be seen in this context to be the tears, shed or unshed, which we all feel welling up within us in moments of sorrow, anguish, unfulfilled yearning, or deeply felt sympathy. It is for this reason that the weeping tone has a distinguished lineage in the tenor voice running back through Caruso to Rubini, with its origins possibly lying, to judge from the recordings of Alessandro Moreschi, in the castrato voice. The valid objections to the musical sob in certain forms and instances was clearly stated by Lauri-Volpi in L’equivoco as being, in the case of “the innumerable vocal mediocrities” who sought to imitate Caruso, “an explosion of the middle voice to the detriment of the higher pitches,” whereas “the weeping of Caruso suffused the whole vocal stream from D to high B natural,” just as did Gigli’s, with no impairment of the higher notes.10 There is evidence, indeed, that the Gigli tear was a spontaneous manifestation in his tone even as a child. As his art matured and his vocal control became complete, he saw in tears the very stuff of lamentation. As Il Giornale degli’Artisti11 put it in Milan, “this tear, which rends to the heart, moves even the most skeptical”. Never a mannerism, never a conscious or deliberately artificial device, never used routinely, the tear arose in Gigli’s singing, or did not arise as the case may be, in the white heat of performance, and it was always contoured to the vocal line. There is no valid musical or aesthetic objection to it, for it represents the tears of all humanity, and they have been legion.

If tears and the gift of the languid sigh are an inherent part of the finest tenor singing in Italian music, interpretation is nevertheless paramount. Much of this depends not only on the singer’s imagination, but on the totality of his vocal resources. In this, Gigli’s almost perfect voice production and the fluency of his messa di voce, with the vocal flexibility that that implied, gave him boundless possibilities. By 1924, he had become in fact the only twentieth-century tenor who has been able to do anything he liked with his voice within the very extensive repertoire of his choosing which, contrary to legend, was at least as much spinto as it was lyric.

To this must be added the inestimable magic of his mezza voce.Far from being the distained falsetto too often mentioned by his critics, or mere crooning as some of them have irresponsibly said, this precious vocal quality, which Rodolfo Celletti has likened to “sighs made of white gold,”12 was nothing less than the celebrated veiled tones, the voice in the mask as it was called, of the great romantic tenors of the nineteenth century from Rubini to Gayarre and Angelo Masini. Produced with the lips scarcely parted so that the tone passed through the masking veil of the face, this tone was so resonant and full that it could be heard clearly in the Verona Arena when it was packed with more than forty thousand people, nearly twice its usual capacity, to hear Gigli, and no voice enhancement or amplification was involved. The production of this tone depends on varying degrees in the depth of engagement of the vocal cords in the act of phonation. Gigli was so adept at this elusive mechanism that, with his mezza voce integrated with his full voice in crescendo or decrescendo according to the tenets of the Italian school as outlined by Lauri-Volpi in L’equivoco,13 he could actually execute crescendos within his mezza voce,ravishing his tone with some of the most extraordinary vocal effects ever heard, as in his supposed aspirates or, more sensationally, in his 1936 recording of “È la sòlita storia del pastore” from Cilèa’s L’Arlesiana, where the atmospherics of the recording are so incredible that we feel that we can reach out and touch the shepherd boy while breathing the fragrant air of his pastoral setting.

This tone, which Gigli brought to a pitch of development never otherwise known, though it can be heard also in the recordings of many other tenors including Caruso, Anselmi, Lauri-Volpi, Tagliavini, di Stefano, and Corelli, is invaluable for purposes of conveying ethereality, elegy, reverie, or the tenderness of sympathy or caress. Outstanding examples of it in Gigli’s singing are his 1931 recordings of “Mi par d’udir ancora’ from The Pearl Fishers and the Dream from Massenet’s Manon. Another is his 1932 recording of the “Chanson Hindoue” from Sadko; but it softens also many of his other performances, adding to them qualities of unearthly beauty like so many sighs inlaid with mother-of-pearl.

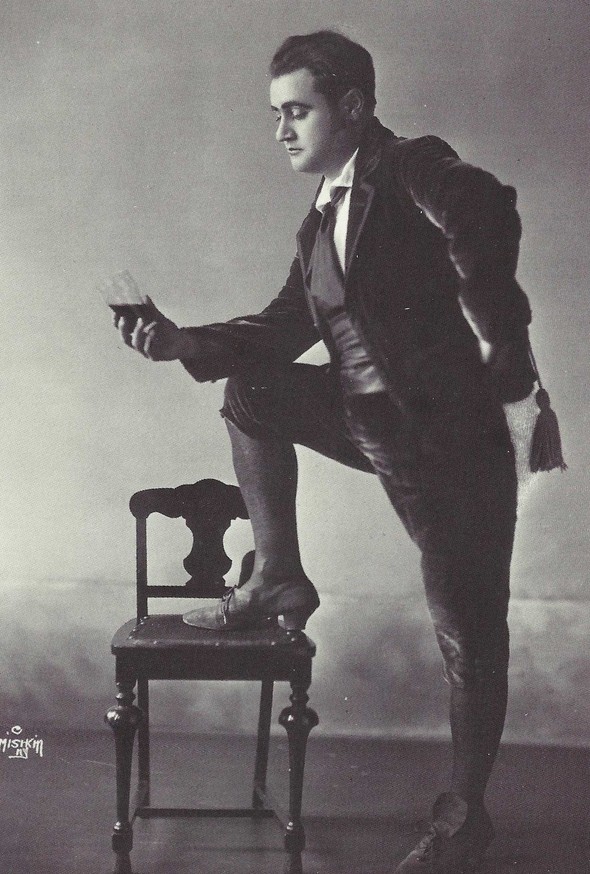

With so rich a vocal organization at his command, Gigli was splendidly equipped to realize the drama of his roles, arias, and songs with a freedom denied to his colleagues. “Art must be a living thing; it can never rest content with its past achievements. It must change and grow,” he said.14 On another occasion he insisted: “I am Gigli and I sing Gigli. To sing the same aria the same way twice, that is of the schools and of the professors. Gigli is not of the schools.”15 If, he said, he had to sing an aria four times in a recital, each time he would sing it differently. His recordings then, are not so much an ideal representation of his art frozen in time as an encapsulated moment in his progress through it. Thus in 1918 he sighed “Spirto gentil” as a moving monologue of Fernando’s inner anguish, with an audacious flourish only at the cadenza; in 1921 he glowingly realized it. He recorded ‘E lucevan le stelle” from Tosca four times commercially, and each is different. The same can be said of his three recordings of even so exacting a piece as “Giunto sul passo estremo” from Mephistofele. In his 1918 recording, his tones are ethereal and elegiac; in that of 1921, he is deeply introspective, registering a very private interior sorrow; in 1927, with great beauty of voice and finesse of phrasing, he is more expansive, successfully externalizing and communicating interior feelings.

Hermann Broch once wrote that all “true writing,” and hence by inference all true dramatic art, must deal with “eternal” things, with “the most basic human experiences, human birth, growth, eating and sleeping, love-making, and death”.16 It was around such things that Gigli constructed his ever-changing, ever-deepening interpretations in both opera and song. Love, in all its fires, tears, and nuances, its many moods and transmutations, is exhaustively examined and portrayed in his recordings, as also are the elegiac qualities of death and mourning, and the vivacity of living, feasting, merry-making, and hope.

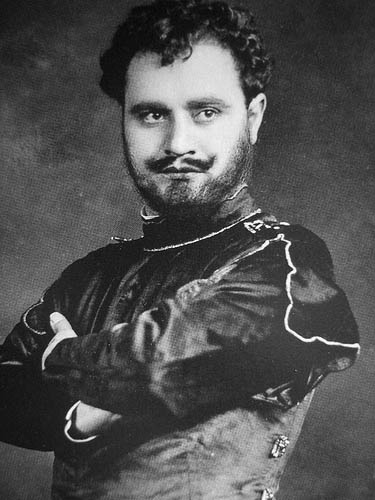

In Gigli’s complete recordings, each portrayal is a living, wholly convincing being; and each is drawn in individual, not conventional, terms. In Pagliacci, his Canio, sung in 1934 in terms of the greatest vocal splendor, is not the vengeful husband of melodramatic operatic cliché, but a very human Calabrian man who trusts and adores his wife, warns off any potential trespasser, is anguished by her betrayal but not vengeful, and is driven to a delirium of revenge only by the re-enactment of the play within the play. In La Bohème, his Rodolfo is the very image of the youthful Bohemian poet and lover for whom all things are fraught with a certain desperation of circumstance. In this world, love with its promise of hope and joy, is a radiant but passing fulfillment; parting and death become agonies fretted with tenderness and tears. Cavaradossi in Tosca is one of Gigli’s most strikingly original impersonations. Nothing else like it exists on disc. For the young cavaliere-painter, as Gigli depicts him, “Recondita armonia” becomes a single moment of reverie filled with hope and amorous expectation. After his encounter with Angelotti, Cavaradossi becomes convinced that he is doomed and in all his subsequent singing, in the love duet as much as in the second and third acts after Scarpia has acted, Gigli’s tone bears a nacre of melancholy apprehension. It is an outstanding and valid interpretation of Puccini’s score and of the libretto that assigns the springs of the opera’s action, not to Scarpia or Tosca, but to Cavaradossi in the fateful decision he takes to help Angelotti.

In Gigli’s complete recordings, each portrayal is a living, wholly convincing being; and each is drawn in individual, not conventional, terms. In Pagliacci, his Canio, sung in 1934 in terms of the greatest vocal splendor, is not the vengeful husband of melodramatic operatic cliché, but a very human Calabrian man who trusts and adores his wife, warns off any potential trespasser, is anguished by her betrayal but not vengeful, and is driven to a delirium of revenge only by the re-enactment of the play within the play. In La Bohème, his Rodolfo is the very image of the youthful Bohemian poet and lover for whom all things are fraught with a certain desperation of circumstance. In this world, love with its promise of hope and joy, is a radiant but passing fulfillment; parting and death become agonies fretted with tenderness and tears. Cavaradossi in Tosca is one of Gigli’s most strikingly original impersonations. Nothing else like it exists on disc. For the young cavaliere-painter, as Gigli depicts him, “Recondita armonia” becomes a single moment of reverie filled with hope and amorous expectation. After his encounter with Angelotti, Cavaradossi becomes convinced that he is doomed and in all his subsequent singing, in the love duet as much as in the second and third acts after Scarpia has acted, Gigli’s tone bears a nacre of melancholy apprehension. It is an outstanding and valid interpretation of Puccini’s score and of the libretto that assigns the springs of the opera’s action, not to Scarpia or Tosca, but to Cavaradossi in the fateful decision he takes to help Angelotti.

Pinkerton in Madama Butterfly may be a comparatively minor role for Gigli but it is one of his most subtle and imaginative impersonations. He presents Pinkerton, not as the devil-may-care Yankee of operatic stereotype, but as a sophisticated American officer who is genuinely and even deeply drawn to his Japanese bride, so that he treats her gently while being sufficiently worldly to expect, after his entrancing oriental interlude has passed, to take an American wife. In this way, the clash of cultures is emphasized with Pinkerton’s sophistication set against Cio-cio-san’s naive and ultimately tragic devotion.

Similarly in Cavalleria Rusticana, Gigli presents a Turiddu who is fundamentally in love with Santuzza while lying, a bewitched and bemused Sicilian, under the irresistible allure of Lola’s sensuous spell. In the duet, as Gigli sings it, Turiddu spurns Santuzza only reluctantly. In the brindisi he already realizes, as Herman Klein remarked that this will be his last song on earth, and at the end his concern for Santuzza wells up in him in a flood of tears and anguish. In Andrea Chénier, one of the greatest of all Gigli impersonations, he achieves what no other tenor has achieved, a harmonious blending of the soaring rhetoric of Giordano’s score with the lyric poetry and inner death-wish that distinguished the historical Chénier. In Un Ballo in Maschera, the characteristic Verdian fire informs the courtly frivolity and heedless amorous ardor of Gigli’s Riccardo. In Aïda, with an interpretative percipience that has too often been ignored, he presents a Radamès who is a lover first, a soldier second, not of course a dishonorable soldier but one who, after he has walked into Amonasro’s trap, politely refuses the blandishments of Amneris and remains true to Aïda to very death.

Idiom was Gigli’s constant artistic preoccupation, as much in his songs as in his operatic recordings. He makes stylistic distinctions not only between the different

composers, but between their different works. His Turiddu and his Fritz Kobus seem to inhabit different vocal worlds, as do his Des Grieux in Puccini’s Manon Lescaut and his Pinkerton, or his Alfredo in La Traviata and his Riccardo in Un Ballo in Maschera. When he sings French opera in French he makes a sincere and largely successful attempt to master the Gallic idiom, as in his aubade from Le Roi d’Ys or his duets with Lucrezia Bori from Roméo et Juliette. When he sings it in Italian, he enters that stylistic convention that had its roots in the Théâtre Italiens in Paris by which the Italians took French opera to themselves, usually with the composer’s consent, and his style and idiom consequently become more but not inappropriately Italianate.

Atmospherics and drama, dynamically conceived, are the outstanding aesthetic characteristics of Gigli’s recordings. It may be true that his career coincided with the phase of decadence in the whole body of Italian operatic composition from Caccini and Monteverdi to Puccini, Mascagni, Giordano, and Cilèa but, as happens so often in any art, especially in the arts of performance, the moment of decadence was also that of one of its finest flowerings. In our endeavors to keep opera alive, we cannot do better than to delve into Gigli’s recordings, not to imitate them, but to find in them certain fertile seeds with, as Gigli himself once wrote in another context, “the fixed purpose of bringing about the triumph of the pure and the beautiful”.17

[fancy_box title=”Colin Bain Remembered”]Colin Caldwell Bain (1926-2007) was born in Liverpool, Sydney, Australia, on 22 September 1926. At the age of 16, he began what was to become a lifelong love for the singing of the great Italian tenor, Beniamino Gigli. In time, Colin met the Gigli family, and was to become the world authority on him. It was with Beniaminos’s daughter Rina, that Colin was authorised as the official biographer of her father’s life. He had several scholarly articles published about Gigli in America and Australia. At the time of his death, on 18 June 2007, Colin was putting the final touches to his biography on Gigli.

[/fancy_box][info_box]This article was first published in the ARSC Journal XXX / ii 1999, written by Colin Bain. Sadly, Bain passed away in June 2007. It was then published on Grandi-Tenori in commemoration of Gigli and his passing in 2009. It was republished here on Opera Vivrà on the 26th of February, 2016.[/info_box] [toggle title=”Footnotes”]

- Letter Fred to Will Gaisberg, Milan, 17 May 1918

- William R. Moran, (Ed. ): Herman Klein and the GramophonePortland, Oregon: Amadeus Press, 1990 p.522

- Alan Blyth (Ed.): Opera on Recor Melbourne: Hutchinson, 1979 p.175

- Letters, Mascagni to Gigli 1921, Giordano to Gigli 1922, Crimi to Gigli 1932. Telegram, Puccini to Gigli October 1924. Interview with Alessandro Bonci published in Bulletin degli Artisti, Milan, September 1930

- Rosa Ponselle and James A. Drake: Ponselle, A Singer’s Life New York: Doubleday, 1982 p.87

- Author’s interviews with Toti dal Monte, Maria Caniglia, Sara Scuderi, Mafalda Fàvero, Gianna Pederzini, and Marina Chaliapine-Freddi. Also Tito Gobbi: My Life London: Macdonald and Jane’s, 1979 pp.79-80

- The New York Sun, 8 December 1931

- Anna-Lisa Björling and Andrew Farkas, Juss Portland, Oregon: Amadeus Press, 1996 p.115

- Giulio Gatti-Casazza: Memories of the Oper London: John Calder, 1977 pp.308-309

- Giacomo Lauri-Volpi: L’equivoco Rome: Edizioni Corbaccio, 1939, p.279

- Il Giornale degli Artisti, Milan, December 1918

- Rodolfo Celletti: Gigli and the Opera, Milan, 1978

- Giacomo Lauri-Volpi: L’equivoco, p.280

- Beniamino Gigli: “Million Dollar Top Notes”, The Musical Digest,February 1929

- The Denver Post, 16 October 1924

- Hermann Broch: The Spel New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1987 p.383

- Beniamino Gigli: Letter to The New York Times, 25 November 1921