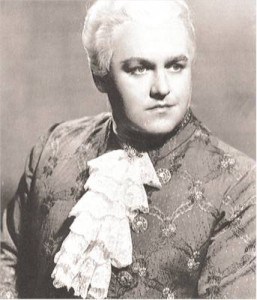

Described as “the Nordic archangel endowed with a celestial high C”, Jussi Björling was born in Stora Tuna, a small town a few kilometers from Stockholm, Sweden, on the 2nd February 1911 into a musical family. By the age of eight, as an already accomplished boy-soprano, he was on tour with his father, an established tenor, and two brothers in Sweden, other countries and also as far away as the U.S.A. While in America the Björling Vocal Quartet, as the group was known, recorded excerpts for the American Columbia Recording Company. These February 1920 discs feature four solos by the young Jussi: documents which provide a unique history of the Björling voice on record over a recording period of forty-one years in a life-span of forty-nine.

Described as “the Nordic archangel endowed with a celestial high C”, Jussi Björling was born in Stora Tuna, a small town a few kilometers from Stockholm, Sweden, on the 2nd February 1911 into a musical family. By the age of eight, as an already accomplished boy-soprano, he was on tour with his father, an established tenor, and two brothers in Sweden, other countries and also as far away as the U.S.A. While in America the Björling Vocal Quartet, as the group was known, recorded excerpts for the American Columbia Recording Company. These February 1920 discs feature four solos by the young Jussi: documents which provide a unique history of the Björling voice on record over a recording period of forty-one years in a life-span of forty-nine.

After initial studies under the tutelage of his father, Björling proceeded to the Royal Opera School at the Stockholm Conservatory where he furthered his studies with the baritone John Forsell. Björling always spoke highly of Forsell’s lessons, adding that it was later through the Scottish tenor Joseph Hislop that he learnt the technique and voice placing to produce his brilliant upper register. By the age of nineteen, he had already made his first commercial recordings; a series of Swedish songs and a selection of operatic arias sung in Swedish. In 1932 he debuted at the Stockholm Royal Opera House in the minor role of The Lamp Lighter in Puccini’s Manon Lescaut.

His first lead roles were those of Don Ottavio in Mozart’s Don Giovanni, The Count in Rossini’s Il Barbiere Di Siviglia and surprisingly assuming also the daunting role of Arnoldo in Rossini’s William Tell. By the mid-thirties, he was already an international star and was performing successfully in the major European Opera Houses of Vienna, Salzburg, Prague, Budapest and also London’s Covent Garden. In 1937 he made his American debut in Chicago in Verdi’s Rigoletto, followed by his first Metropolitan Opera House performance as Rodolfo in Puccini’s La Boheme.

His appearances continued uninterrupted on both opera and concert stage up to a few days before his death. Throughout his career, despite reticent to rehearse and an inability to control his drinking, his performances were marked by innate musicianship, a sweeping sense of legato in the voice and ever present clarion tones.

My own first encounter with the Jussi Björling voice was from a ten-inch double sided 78, red-label HMV record of two arias from Millöcker’s The Beggar Student and Offenbach’s La Belle Hélène. Recorded in 1938, this record had somehow slipped into my paternal grandmother’s collection which allowed me the first sampling of the sound of the tenor voice and also initiated me into the world of opera. The collection, though small, was well chosen. It focused on earlier pre-electric discs and featured the voices of Bonci, Anselmi, de Lucia, an odd Gigli and the mandatory amount of Caruso recordings. To my grandmother tenors were Italian! At most, they just may have been Spanish! I well remember her introducing me to the caressing diminuendos of Miguel Fleta’s rendering of the Act 1 aria from Bellini’s I Puritani. During my early teens, it was she who lovingly and patiently trained my eager receptive ears to not only the oboe-like tones of Bonci, Anselmi and Fernando de Lucia but also to the Vesuvius crater-like sounds of the late dark Caruso voice. If Bonci, Anselmi and de Lucia evoked the oboe and Fleta the violin, Caruso, in his later years, could be likened to the sonorous sounds of the cello. My grandmother would categorically not admit to having acquired the Björling record herself. How it came into the collection remained an untold story.

Despite the fact that I had already begun, through my meagre pocket-money allowance, to acquire one or two records of my own, (Mario Lanza, through his films, being my prized purchase) the collection was essentially geared to my grandmother’s not too easily satisfied taste. Master singers of the like of Bonci, Anselmi, De Lucia and Fleta were to her ears “a delight to listen to”. Gigli, despite his sweet tones was considered “lachrymose and over emotional”; Martinelli “nasal”; and to my disappointment, my newly discovered hero Lanza was disdainfully dismissed as “loud and lacking in musical scholarship”. My grandmother was a formidable woman! She was not to be contradicted, and one did not question her judgements. To her, Caruso’s voice remained the “most perfect vocal instrument”, providing “the most glorious tenor-singing ever heard.” However, listening to the Jussi Björling rendering of The Beggar Student song played on an old wind-up gramophone with steel needles provided a thrill which, despite her initial aversion to his name and nationality (she could not comprehend a tenor coming from cold Nordic climes) caused her to produce half tones of praise if not exactly enthusiasm. If her reaction was not one of enchantment, mine was certainly one of intoxication. Response to voices remains, above all, a matter of personal chemistry. The bewitching élan with which the young Björling joyously journeys through the aria’s arduous tessitura, plus his surprisingly technical mastery remains, for me to this day, a wonderful example of the sheer magic that impeccable singing can convey. The final high D-flat has the cleanliness of a silver rapier and the crystal clarity of the reflective waters of the tenor’s ancestral Scandinavian fjords. Giulietta Simionato was right in later referring to Björling’s voice as one of “crystal and honey”.

Despite the fact that I had already begun, through my meagre pocket-money allowance, to acquire one or two records of my own, (Mario Lanza, through his films, being my prized purchase) the collection was essentially geared to my grandmother’s not too easily satisfied taste. Master singers of the like of Bonci, Anselmi, De Lucia and Fleta were to her ears “a delight to listen to”. Gigli, despite his sweet tones was considered “lachrymose and over emotional”; Martinelli “nasal”; and to my disappointment, my newly discovered hero Lanza was disdainfully dismissed as “loud and lacking in musical scholarship”. My grandmother was a formidable woman! She was not to be contradicted, and one did not question her judgements. To her, Caruso’s voice remained the “most perfect vocal instrument”, providing “the most glorious tenor-singing ever heard.” However, listening to the Jussi Björling rendering of The Beggar Student song played on an old wind-up gramophone with steel needles provided a thrill which, despite her initial aversion to his name and nationality (she could not comprehend a tenor coming from cold Nordic climes) caused her to produce half tones of praise if not exactly enthusiasm. If her reaction was not one of enchantment, mine was certainly one of intoxication. Response to voices remains, above all, a matter of personal chemistry. The bewitching élan with which the young Björling joyously journeys through the aria’s arduous tessitura, plus his surprisingly technical mastery remains, for me to this day, a wonderful example of the sheer magic that impeccable singing can convey. The final high D-flat has the cleanliness of a silver rapier and the crystal clarity of the reflective waters of the tenor’s ancestral Scandinavian fjords. Giulietta Simionato was right in later referring to Björling’s voice as one of “crystal and honey”.

Despite my grandmother’s acceptance of this intruder into her Mediterranean world of revered tenors, she still raised an eyebrow and lamented that “his performance lacked warmth” and that the voice itself reflected “the coldness of the icy North.” Her complaint that Björling was a cold singer was one which was oft-repeated by many a critic throughout his career. Italian audiences, accustomed perhaps to more emotional tear-jerked Gigli interpretations, together with leading critics of that land including Rodolfo Celletti and others, always found Björling’s singing to be “cold and with little expression”. Giacomo Lauri Volpi in his Voci Parallele, an informative if personally prejudiced survey of operatic voices, reduces Björling to a mere footnote. While the Swedish tenor’s interpretations on stage may have lacked emotion and dramatic overtones, his Nordic restraint still enabled him to sing with great expression, without ever breaking the vocal line. It was perhaps this ascetic discipline that allowed him never to take liberties with the music.

Björling’s voice did indeed lack the warm Mediterranean sun-filled qualities of the Italian or Spanish school of singing, but his sense of legato and his lyrical treatment of line together with a resplendent timbre, always, as Robert Merrill correctly stated “bewitched all who heard him”. The American baritone goes on to refer to Björling’s “golden-timbre” adding that “he was an inspiration to work with”. Many of his other colleagues have constantly made reference to Björling’s interpretations as “singing lessons”. Dorothy Kirsten, in her autobiography, refers to Björling as “the greatest tenor of my generation; the most glorious sound I have ever heard.” Bass, Boris Christoff considered Björling’s voice “the most beautiful among living tenors”, while Blanche Thebom, insisted that “there has never been such a unique quality.” Surely the most complimentary statement comes from baritone Cornell MacNeil who, when singing Lescaut to Jussi Björling’s Des Grieux at the Met, was so astounded at the tenor’s Third Act plea, No Pazzo Son, that he was unable to sing his own lines. “He just staggered me with his vocalism.” What his voice lacked in warmth, Björling compensated with haunting melancholic sounds. His emotions were there, but they were always conveyed within the voice. His was, as one critic once wrote, “a voice heavy with unshed tears”.

Tenors rarely, if ever, speak highly of other tenors. Yet Björling always admired and stood in awe of Caruso. His wife, Anna-Lisa, herself an accomplished soprano, on the other hand was more of a Gigli fan. Often during intermissions between one Act and another, she would rush to her husband’s dressing room and exclaim ” Jussi, more Gigli … less Caruso”. Björling also generously admired many of his contemporaries, especially the Americans Jan Peerce and Richard Tucker, but above all, he held in high esteem Giuseppe Di Stefano. After Di Stefano’s brilliant 1948 Metropolitan Opera House performances in Massenet’s Manon, the two met and Björling asked Di Stefano to pass on to him the secret of his top diminuendo in Il Sogno. Di Stefano, in his autobiography, recounts that the tutelage was unsuccessful! He however goes on to narrate that later lessons imparted to him by the Swede on how to produce steel cutting high notes were equally fruitless!

Another singer admired by Jussi Björling was Mario Lanza. Björling had originally been contacted by MGM to star in the film The Great Caruso but the negotiations fell through at an early stage. When the film was issued in 1951, Anne-Charlotte, Björling’s daughter recounts that her father had taken her to see the film and that she was very much taken in by both Lanza’s looks and singing. As she remarked to her father “he’s so handsome and he sings fantastically”, the sole answer she got back was a grunted “Hmm!” Later that year, the two tenors met at Lanza’s Hollywood home. Besides their mutual admiration (Lanza also thought very highly of Björling) they also shared a common predilection for alcohol. Terry Robinson, in his Lanza biography, recounts how the two sat listening to each other’s recordings, shedding tears, while getting through a number of whisky bottles in a few hours.

In his forty-one year long recording career, Jussi Björling left a rich discography. Through this, one is able to trace the development and changes in his voice in time. The recorded legacy includes not only the commercial recordings made for Swedish HMV, HMV and later RCA and Decca, but also an invaluable collection of live performances and concerts from stage and concert appearances in the U.S.A. and Sweden. The early freshness and poetic radiance of the voice matured in the later years to a heavier darker timbre. Always, however, his pure attack, cleanliness of tone and remarkable breath-control remained evident. Although the voice gained in strength and weight over the years, the vibrancy of his brilliant tenor never deserted him, and to the end, he always sang with heroic ardour.

From the commercial recordings it is difficult to signal out any of the single arias or songs. All are examples of the impeccable quality of this supreme singer. However, one album of duets with Robert Merrill, recorded in November 1950, stands out. The two voices blend meltingly in a varied range of music, conducted by Renato Cellini, from the melodiously haunting interpretation of Bizet’s “Au Fond Du Temple Saint” to the dramatic declamatory oath scene from Verdi’s Otello. For this latter duet, Björling was intent on creating a Caruso-like tone in his voice. Robert Merrill recalls their consistently listening to, at Björling’s insistence, the Caruso-Ruffo version, over and over again, with Björling stating “I want it to sound like the Caruso-Ruffo record”, to which Merrill answered “we’ll try, but it will still be the Björling-Merrill version!”. Many critics have since written that if the Caruso-Ruffo version did not exist, the Björling-Merrill version would certainly be the exemplary choice among the recorded versions of this music.

From the complete opera sets recorded in the fifties, Il Trovatore with Milanov, Warren and Barbieri remains an exemplary rendition; while for sheer fireworks, the July 1959 Turandot with Brigit Nilsson and Renata Tebaldi, remains one of the most exhilarating interpretations of this opera on disc. The Riddle Scene between Björling and Nilsson provides singing that is absolutely hair-raising and spine-chilling. Many consider the Sir Thomas Beecham 1956 Boheme with Björling, Merrill and the exquisite Victoria De los Angeles as the finest version of this opera on record. However, to convince all and sundry that Björling was not a cold singer, the 1957 recording of Cavalleria Rusticana with Tebaldi and Ettore Bastianini, presents a passionate example of throbbing singing, with Björling actually sounding as if he is a genuine hot-blooded Sicilian.

Jussi Björling’s repertoire consisted of fifty-five operatic roles plus a considerable number of Italian, German, French and Swedish songs. Perhaps his greatest roles on stage were Faust, Romeo and Riccardo in Verdi’s Un Ballo In Maschera. Unfortunately, none of these roles were recorded commercially in complete-opera form. However, Un Ballo In Maschera with Björling as Riccardo came close to being preserved for posterity. In July 1960, three months before the tenor’s death, Decca assembled a notable cast including Nilsson, Giulietta Simionato and Cornell MacNeil, together with Björling, in Rome, to record this work under the direction of Georg Solti. Whether it was incompatibility between Solti and Björling, or whether (according to Producer John Culshaw) it was Björling’s inability to perform as he was under the influence of alcohol that caused the recording sessions to be cancelled, still remains unclear. What with the intense summer heat of Rome and Solti’s selfishness, together with the tenor’s ailing health, the circumstances were simply not ideal for the manifestation of this recording project. However, the real reasons for the cancellation of the project remain untold.

Jussi Björling’s repertoire consisted of fifty-five operatic roles plus a considerable number of Italian, German, French and Swedish songs. Perhaps his greatest roles on stage were Faust, Romeo and Riccardo in Verdi’s Un Ballo In Maschera. Unfortunately, none of these roles were recorded commercially in complete-opera form. However, Un Ballo In Maschera with Björling as Riccardo came close to being preserved for posterity. In July 1960, three months before the tenor’s death, Decca assembled a notable cast including Nilsson, Giulietta Simionato and Cornell MacNeil, together with Björling, in Rome, to record this work under the direction of Georg Solti. Whether it was incompatibility between Solti and Björling, or whether (according to Producer John Culshaw) it was Björling’s inability to perform as he was under the influence of alcohol that caused the recording sessions to be cancelled, still remains unclear. What with the intense summer heat of Rome and Solti’s selfishness, together with the tenor’s ailing health, the circumstances were simply not ideal for the manifestation of this recording project. However, the real reasons for the cancellation of the project remain untold.

It is perhaps more from the riches of the non-commercial recordings that one can fully appreciate Björling’s vocal colouring and his ability to combine silver trumpet tones with melting diminuendos. The three great roles of Faust, Romeo and Riccardo which were omitted from Björling’s commercially recorded legacy are all offered, in part or whole, in live recorded versions. What Björling would have sounded like in the Solti Un Ballo In Maschera recording is hinted at in performances which come from 1940 in San Francisco and the Met together with a 1950 New Orleans version. However, the prime prize is the February 1st 1947 Met performance of Romeo and Juliet with Bidu Sayao. This is surely one of those state of grace performances. Sayao is luscious and treacle-like in a role that was perfectly suited to both her beautiful vocal and physical qualities. Despite his cherubic looks Björling may not have acted the greatest Romeo, but his singing in this performance is near perfection. The Act II duet “Ah ! Ne Fuis Pas Encore” is sheer magic.

Throughout his career Björling was extremely careful in the choice of his repertoire. He took on few heavy roles, and sang those only on rare occasions. Towards the end of his career he was planning to tackle the roles of Otello and Lohengrin. Although he would have surely been resplendent in both Carmen and in the role of Andrea Chenier, he never in fact, learnt these parts, although the 1951 RCA Rise Stevens-Jan Peerce recording of the Gounod opera was originally planned with the Swede in the tenor role. The most demanding roles which Jussi Björling performed on stage were Rhadames (thirty-one performances) and Manrico (sixty-seven performances).

While the commercial recording of Il Trovatore, is nothing short of impeccable, his live 1941 Met performance and the later more dramatic 1960 version at the Stockholm Opera House, introduce us to a more heroic interpretation of the role. In the lyrical moments Björling is a true troubadour, while in the more dramatic scenes of the opera he is a stalwart soldier with a voice as cutting as the metal of his sword. Once again these are performances to be cherished. In November 1955 Björling paired with Callas for two performances of this opera at the Chicago Lyric Theater with Ebe Stignani and Ettore Bastianini completing the cast in the first performance. This must have been an absolutely unique rendering of the opera. Rumours have it that attempts were made to record the performance but that the recording apparatus was inadvertently unplugged!

My own favourite Jussi Björling documented live performance is that of the November 1st 1959 Stockholm Opera version of Manon Lescaut. By this time, as the tenor confessed to his son Lasse he had “burnt the candle at both ends”. He was a tired and sick man. Yet listening to that bronze tone of his interpretation makes it hard to believe that within a year the great tenor would be dead. Nowhere on record will you find such intensity and soaring sounds of continuous unbroken rich vocal splendour. The tenor’s plea to the Ship’s Captain to join Manon on her journey to America remains one of the most exciting of documented performances of tenor singing. Not surprising that Cornell MacNeil forgot his lines ! Nor was it surprising that at the same opera’s performance-broadcast, years earlier, at the Met, Amelita Galli-Curci cabled Björling “listening in with great pleasure … BRAVISSIMO.” Worthy also of note in the series of live recordings, are many of the excerpts from his Gröna Lund Tivoli Summer Concerts.

My own favourite Jussi Björling documented live performance is that of the November 1st 1959 Stockholm Opera version of Manon Lescaut. By this time, as the tenor confessed to his son Lasse he had “burnt the candle at both ends”. He was a tired and sick man. Yet listening to that bronze tone of his interpretation makes it hard to believe that within a year the great tenor would be dead. Nowhere on record will you find such intensity and soaring sounds of continuous unbroken rich vocal splendour. The tenor’s plea to the Ship’s Captain to join Manon on her journey to America remains one of the most exciting of documented performances of tenor singing. Not surprising that Cornell MacNeil forgot his lines ! Nor was it surprising that at the same opera’s performance-broadcast, years earlier, at the Met, Amelita Galli-Curci cabled Björling “listening in with great pleasure … BRAVISSIMO.” Worthy also of note in the series of live recordings, are many of the excerpts from his Gröna Lund Tivoli Summer Concerts.

Both critics and singers to this day, fifty years after his death, continue to pay respect and homage to Björling. Domingo refers to his “regal sound” and considers him ” an inspiration.” His was the high tenor voice “par excellence”. He once told his accompanist “I want it transposed”. To the pianist’s answer of “how low?” Björling answered “No, no … not lower, higher … it is the low notes I am worried about.” Despite his addiction to alcohol, his memory remained unaffected as did his liquid tone, vocal quality and near perfect breath control. As all the great tenors who came after Caruso, Björling was also christened The New Caruso or more accurately The Swedish Caruso. What with the American Caruso (Mario Lanza), the Pocket-Sized Caruso (Joseph Schmidt), the English Caruso (Tom Burke) and many others, it seems that there remains an indefatigable need to compare each new-comer in the field to the incomparable Neapolitan.

Of all the post-Caruso tenors, without doubt, it is Jussi Björling who rises to the greatest heights. Although their vocal characteristics were dissimilar, they shared many qualities. Dorothy Caruso repeatedly stated that of all the voices she had heard it was Björling’s instrument which reminded her most of her husband’s singing. On the 16 February 1951, after a Metropolitan Opera House performance by Björling, Dorothy Caruso presented the Swedish tenor with the costume Caruso had worn as The Duke in Verdi’s Rigoletto. “You are the only one worthy to wear Rico’s crown.” She was, of course, perfectly right!