Verdi is personified melodrama and heroic tenors in Verdi’s operas are vehicles driven by the genius of Busseto to portray human life, better still human drama. The plots border on exaggeration and absurdity, at times. The acts are as brief as necessary to maximize dramatic effects.

Verdi is personified melodrama and heroic tenors in Verdi’s operas are vehicles driven by the genius of Busseto to portray human life, better still human drama. The plots border on exaggeration and absurdity, at times. The acts are as brief as necessary to maximize dramatic effects.

In melodrama, Wagner saw a hyperbolic, insane adventure or “a brilliant lie” as he wrote harmonic-melodic music dramas with a Saxon vein. Wagner and Verdi had the same age but never met, although Verdi became acquainted with Cosima Wagner, his wife. Both composers kept each other at a distance. On hearing of Wagner’s death in 1883, Verdi exclaimed “Sad! Sad! Sad!…a name that leaves a most powerful mark on the history of our art”.

Verdi purchased the scores of Wagner’s operas. He was among spectators at a performance of Lohengrin in Bologna and Tannhauser in Vienna but did not take much from them. He grew indignant at the charge of “Wagnerism” in Otello. Nevertheless, he studied and assessed the music and drama of Wagner. He reveled in the Heldentenor’ supremacy and admired the Wagnerian infinite hero who would rather lose himself, like Siegfried, in the unknown of the forest.

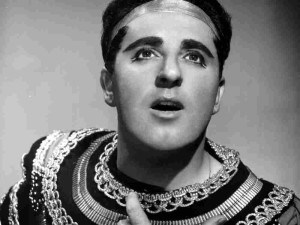

Hence, at first sight, should one readily agree that Manrico, the hero (and tenor) for excellence in Verdi, be included in such a circle of infinity and solitude? The answer is not simple. The Heldentenor falls into nihilism and the Wagnerian tenor is originally a misogynist, a fatal trait that makes him a victim. He reduces the rock-like material of his voice to inevitable friability. Fundamentally, one should perceive the heroic tenors in Verdi as possessing a solid virility, even if transparent only. Therefore, Manrico will forever be in pursuit of a silvery, blade-like virile voice every tenor portraying the part should possess (as Lazaro, Martinelli, Roswaenge, and Lauri-Volpi did) without which Manrico would abdicate and relinquish his own nature.

In Luisa Miller, Rodolfo does not disdain affectionate demonstrations (in which Schipa excelled) but resolves the cabaletta with lucent golden arrows, for which Lazaro and Lauri-Volpi were the archetypes, displaying unmatched chivalrous temerity. Don Carlo, heir to the court of Spain, is a pallid and melancholic hero (or an anti-hero if one prefers) who shows an ambiguous and decadent charm, so well portrayed by the fleshy and cordial notes of Bergonzi and those penetrating ones of Picchi. Alfredo (Traviata), the Duke of Mantua (Rigoletto), Riccardo (Ballo) and Don Alvaro (Forza) suffer of amorous maladies exhaustively and do not follow the heroic tradition. The sweet, lyrical sounds of Kraus, the youthful Di Stefano, Pavarotti and “la voz de oro” Filippeschi paid great homage to these anti-heroes.

After the bandit Ernani and the adventurous, lone Manrico, was there still space left for another heroic tenor? Did not the Troubadour, champion of heroism and melancholy, fill all spaces and exhaust all possibilities? This heroic character, well molded and sculptured, could not disappear overnight. The characters that followed him prepared the end (Otello) after a last-minute restoration (Radames). Arrigo of The Sicilian Vespers initiated the breaking down of such a compact figure.

The last heroic tenor is Radames, to whom Verdi dedicated an early triumphant scene. Radames’ impotent ending is not as solitary and bloody as Manrico’s. Found guilty of treason, the entombed heroic leader of the Egyptians and Aida, the slave girl, sing together their last hurrah and give up all worldly seductions. So much heroism enticed a myriad of tenor lirico, lirico-spinto, drammatico and a heap of Wagnerians to play and sing the part. We had great tenors of the “espada”, those of the romantic and sensual schools as well as Wagnerian tenors, Roswaenge, Bjorling, Slezak, Patzac and Konya, to honor the Egyptian leader. I must single out the great Aragonese tenor Miguel Fleta, the king of incredible “smorzature” (sound extinguishments), as a superb interpreter of the doomed Radames. Co-starring an inspired soprano Florence Austral, as Aida, in 1923, they recorded a memorable “..O terra addio..” in the tomb scene of the opera Aida.

Many critics consider Otello to be the greatest opera ever written. I feel that some of its musical elements recall Wagner. Its inventive, fluid and complex orchestration made the world point fingers hurriedly at the German composer. Otello, the battle hardened general, is the dramatic hero of the opera. He falls prey to the scheming Iago’s insinuations. He becomes extremely jealous of his wife suspected to be unfaithful and kills her. On learning of her innocence, he is horrified and knifes himself in despair. He utters the last heroic whisper “..ah! un’altro bacio” leaning over the lifeless Desdemona for a last kiss before dying. The dark, dramatic nature of the plot and Verdi’s central tessitura were congenial to baritones turned tenors, who excelled in portraying the dramatis persona. The tenor Del Monaco, with his unique voice for Otello, the ex-baritones Zenatello, Vinay, Guichandut, the middle-aged illustrious tenors Pertile, Martinelli, Lauri-Volpi and the tenors Vickers, McCracken, Domingo, Cossutta paid tribute with their glorious voices to the Verdian dramatic hero. Below a video of Melchior singing Otello (in German):