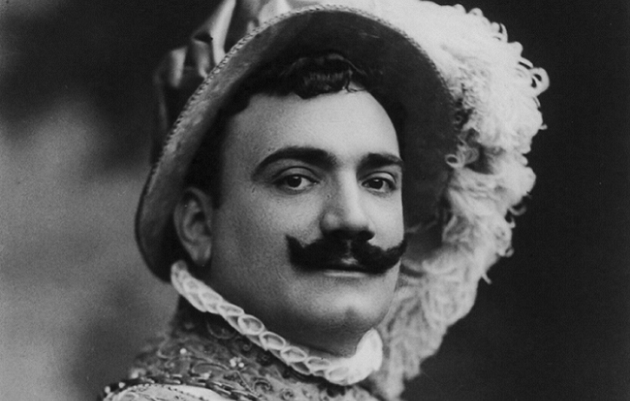

Enrico Caruso was a unique great tenor, without any doubt. I included him in my personal choice of the XX century “avant guard” group of great tenors. The group comprises the Italians Caruso, Lauri-Volpi, Filippeschi, Schipa, the French Thill, the Spanish Fleta, Kraus, the German Melchior, the Danish Roswaenge, the Dutch Windgassen, the Bohemian Slezak, the Slovenian Dermota, the Austrians Patzak and Tauber. My favourite is Lauri-Volpi, a religious, mystic and highly cultured man so unusual for a great tenor.

Some of the rapturous accolades bestowed upon Caruso are: “The voice and style of the XX century,” “The standard of tenor voice supremacy,” “The man of Naples and voice of gold” and “The hero of the Old and New Worlds.” Caruso’s voice was certainly unique for baritone colour, strength, luminosity or “solarità,” ample and natural phrasing. The famous voice, however, had a short extension and difficult vibration. The style was also unique for deep cordiality and humanity. Voice and style extraordinarily conveyed intimate drama on to the stage. On listening to the sound emitted by Caruso, one gets the feeling that the vocal chords were in the heart muscle rather than the larynx and that blood flow activated them. Alas, the sound density and soul intensity finally consumed and shattered the colossus’ life!

Caruso’s times were those of “La Belle Époque” (1900-1914), the old and new Neapolitan songs, which found room in the great tenor’s sweeping repertory together with minor works by Meyerbeer and Gomez, operas now forgotten but kept well alive then. The composer Franchetti was the rival of Flotow, the novelist and librettist Marchetti that of Halevy. The French grand operas Gli Ugonotti and L’Africana of Meyerbeer were running against the Italian Romantic operas of Verdi, in particular Aida, Il Trovatore, La Forza del destino and Rigoletto. Puccini, Giordano and Cilea were composers of the modern interpretive school of opera. They reigned over theatre audiences, ready to get passionate about Tosca’ sweet kisses and languid caresses, Loris’ tears and Maurizio of Saxony’s languor. Debussy was still alive. Mahler brought to the horizon a new world to which Schoenberg conferred dignity in trying to eradicate a prevailing vulgarity. The promoter Diaghilev, the dancers Nijinsky and Ida Rubinstein gave fresh vigor and novelty to ballet music.

How did the mythical tenor phase in the new Europe of artistic sense, delicate tastes, passionate refinements and French boudoirs? He symbolized it from a distant America with cordiality, personality, naturalness, expressive passion and “parlar-cantando.” He created the role of the noble bandit Johnson in La Fanciulla del West by Puccini, a triumph at the Met, co-starring Emmy Destinn and Pasquale Amato under the imperious baton of Toscanini. He enriched the flavour of verismo in opera with his interpretation of Canio in Pagliacci by Leoncavallo, giving proof of a dramatic, vivid and desperate Caruso.

Between 1910 and 1930, a myriad of tenors flourished and some of them were attracted to the orbit of a crestfallen star (Tamagno) and another one resplendent in its full glow (Caruso). New and at times beautiful voices fell under the two stars’ influence as if they had been mesmerized. Seldom they would shine with their own light. Antonio Cortis, one of the last Spanish tenors of international fame, fell victim to an inferiority complex and imitation. He had come from the comprimari. He took the role of Arlecchino in Pagliacci starring Caruso as Canio and reveled in the great singer splendors to the point of becoming a victim for the rest of his career. The public named him the “Piccolo Caruso” as he sang in Tosca, Carmen and Pagliacci with a rounded sound, well seamed in the middle register, and expansive warmth. The excessive pressure upon the air column eventually wore down the diaphragm and lungs. Galliano Masini, with a beautiful and male tenor voice, imitated Caruso in rounding the sounds, baritone-like in the middle register, and hitting the notes through the abdomen. In so doing, the voice accentuated a natural tendency to emphysema and he became known as the” summer tenor”, suffering the winter cold and humidity. Giovanni Martinelli, Beniamino Gigli and Hipolito Lazaro wanted a triumphant establishment of their names and voices at all costs and above any other tenor. Their dream and torment were to be greater than Caruso.

In the theatre, Caruso abused the “voice of the century” heavily. He was infatuated with dark sounds to such an extent that he used to sing on stage and put on records the bass aria “Vecchia zimarra” (La Boheme). For an evening performance, he used to get up early in the morning and taxi an already hardened larynx with a recital of the whole opera! The sound of the cello fired his fantasy. Then family misadventures hit and greatly concerned him. He found solace in practicing voice concentration and pressure. He had in mind to reproduce a sound similar to that made by the great cellists and succeeded in reproducing it with typical voice deportment and pharyngeal flexibility. The sound became a vocal icon but the exercises somewhat darkened the voice.

His whole body, including lungs, diaphragm, ribs and abdomen helped the heart. The pressure exerted upon these organs in emitting the celebrated phrases of Pagliacci and Manon Lescaut used to cause a surge of blood, congesting the singer’s neck and face. During a performance of L’Elisir d’amore at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, he took ill with a simple influenza, causing inflammation of the lungs heavily taxied by constant effort. Eventually an abscess broke out, which got worse and led to his premature death at 48 years of age. The whole world mourned him and stood in shock at the sad news!

The whole world hero-worshipped Caruso and still does to this day. This is a known fact. His voice was of such a value as to catapult him into an orbit of unmatched excellence. This claim does not fully convince me. The reason for my reluctant incredulity (guided by the mind not the heart) is that two factors essentially contributed to Caruso’s immense popularity and adulation. They were the enthusiastic accolade the world gave to Pagliacci and the advent of the gramophone. Canio’s lament fused in Caruso’s voice echoed in all corners of the earth through the gramophone. The lucky encounter with Otello had given lasting glory to Tamagno. The encounter between an opera, the gramophone and a unique voice gave immortality to Caruso. There was perfect identification between Leoncavallo’s music and Caruso’s voice. There was perfect harmony between the acoustic disc and the darkened, pulpy and turgid voice, sustained by abdominal respiration. The gramophone imprisoned the darkened voice and handed it down to posterity. The gramophone would have been of little use earlier to the brilliant voices of Tamberlick, Gayarre, Marconi, Masini, Tamagno, Stagno and Bonci who would have refused imprisonment of their silvery “acuti” in search of space and daylight.

I hardly perceive the famous voice as having possessed a fully lucent bronze in supreme support of role portrayal. The voice could not produce delicacy, elegance, fioriture, pure mezza voce and almost mute whispers. Caruso should have been aware of his vocal limitations to the musical rigors of bel canto and should wisely have chosen roles congenial to his voice. Nevertheless, he sang in Rigoletto as the vain Duke and in Adriana Lecouvreur as the elegant Count with a semi baritone voice, powerful, bronze top notes and fiery accents giving little credibility to the two mellifluous characters and without persuading his audiences. He sang L’Elisir d’amore at the San Carlo in Naples, his birthplace, with a technique and style suitable to verismo operas. In Caruso’s mouth, the celebrated aria “Una furtiva lacrima” acquired passionate amplitude and vibration, wholly unfamiliar to the listeners. The humble little peasant Nemorino emerged with inappropriate authority and majesty.

The Neapolitan critics crucified the famous voice and lamented Fernando De Lucia’s glorious absence. De Lucia had left indelible memories in L’Elisir d’amore, with expert refinements, guiles in vocal technique, virtuosic passages and stylistic coherence. Caruso did not get over the disappointment and swore never to return to Naples. However, he endured frequent and long sea voyages from his adopted America back to Naples. He died there in 1921 with admiration and love for his adored native city.