Some nights when I’m feeling emotionally indulgent, I read terrible plays. These are the sort of melodramatic trash where cloaks, hats, and daggers abound. Outcast heroes woo angelic women, but family strife or jealous rivals ensure tragic outcomes. In short, they’re opera plots without the music to make them bearable. (I love them anyway.)

Some of these plays were written by surprisingly great authors. I have catalogued the success of Victor Hugo’s now-rarely-performed plays as operas in a separate article. Alexandre Dumas also wrote wonderfully angsty Romantic dramas, though no operatic adaptations have survived in the repertoire. But what intrigues me most are the Spanish playwrights of the 1830s — proponents of a short-lived literary movement who are now entirely unknown in the English-speaking world except through Verdi’s adaptations.

The timeline of the Spanish Romantic movement in theatre is compact:

- 1834: La conjuración de Venecia, by Martínez de la Rosa. Macías, by Larra

- 1835: Don Álvaro, o la fuerza del sino, by the Duke of Rivas

- 1836: El trovador, by García Gutiérrez

- 1837: Los amantes de Teruel, by Hartzenbusch

- 1844: Don Juan Tenorio, by Zorrilla

Zorrilla’s play is generally considered the death knell of the ‘liberal’ Romantic movement in Spain. Poets like Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer would keep the spirit of Romanticism alive in Spanish literature, but its theatrical heyday lasted just ten years. Except for Don Juan Tenorio, the most famous plays of the period are largely forgotten — performed extremely rarely and lacking translations.

Enter Verdi, who immortalized not one but three of the important dramas of 1830s Spain. García Gutiérrez was doubly honored: first with Il trovatore in 1853 (based on his most successful drama, El trovador), and then with Simon Boccanegra in 1857 (based on his play of the same name, written in 1843 when the star of Romantic theater was already falling). Giuseppina Strepponi (later to become Verdi’s second wife) translated El trovador into Italian. She may have introduced Verdi to the play. Regardless of how he found it, he must have been impressed. He asked the librettist Cammarano to work with him on the adaptation without having received a commission from any theater. Cammarano died before the project was finished, and Leone Emanuele Bardare completed it. Libretti with multiple authors seem to be a theme. Verdi worked with Piave on Simon Boccanegra (perhaps also inspired by a translation into Italian by Strepponi). But he was unhappy with the finished libretto and commissioned Giuseppe Montanelli to revise it.

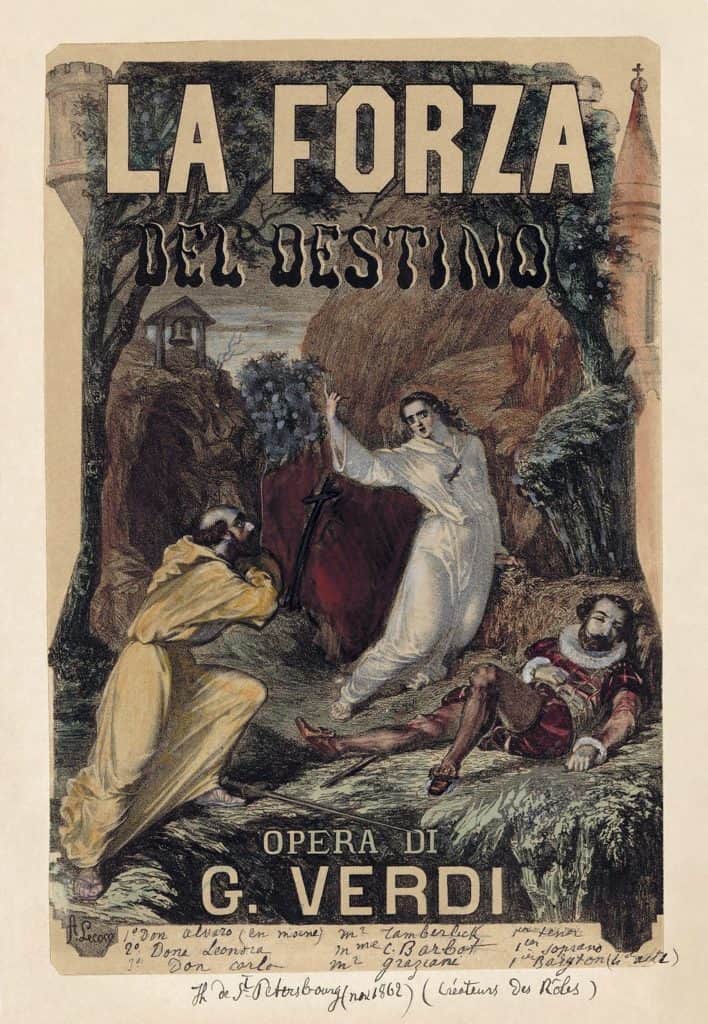

Verdi finished the trilogy (though he likely didn’t think of it as such) by turning to a different playwright of the era: the Duke of Rivas. His Don Álvaro, o la fuerza del sino received its operatic premiere as La forza del destino in 1862. Verdi called Rivas’s play “powerful, singular, extremely vast, and outside of the ordinary,” and he worked with Piave to turn it into a libretto. This involved alterations to the plot, which Rivas publicly denounced. Verdi seemed undaunted, as his 1869 revisions took him even further from the original story. Most notably, the revised version of the opera lets the hero survive. (In the play and the original operatic adaptation, he throws himself off a cliff.)

Verdi finished the trilogy (though he likely didn’t think of it as such) by turning to a different playwright of the era: the Duke of Rivas. His Don Álvaro, o la fuerza del sino received its operatic premiere as La forza del destino in 1862. Verdi called Rivas’s play “powerful, singular, extremely vast, and outside of the ordinary,” and he worked with Piave to turn it into a libretto. This involved alterations to the plot, which Rivas publicly denounced. Verdi seemed undaunted, as his 1869 revisions took him even further from the original story. Most notably, the revised version of the opera lets the hero survive. (In the play and the original operatic adaptation, he throws himself off a cliff.)

All three of these Verdi operas are among the hundred most performed operas in the world. Il trovatore is the most successful (#20 according to Operabase), but its plot is almost always condemned. It is “muddled and confusing,” “truly outlandish,” and “complicated — even incomprehensible.” Tales of love, war, and revenge intersect. The story is rife with absurdities: it depends on such mechanisms as accidental baby-swapping and a convenient poison ring. (La forza del destino has similar unlikelihoods, most notably the scene where the hero dashes all chance of future happiness by accidentally shooting his beloved’s father. It’s practically impossible for a pistol to go off simply because it was tossed onto the ground!) The writers of essays and program notes generally conclude that it succeeds only because Verdi’s music overshadows the weak story. That’s not quite the case: García Gutiérrez’s play was a smash hit in Spain in 1836. The audience of the time loved the absurd plot, even without a great score to carry it. But while I still enjoy reading the play, it’s certainly ill-suited to modern tastes. The Spanish Romantic dramatists have Verdi to thank — not for turning flops into successes, but for turning plays that were popular in their (brief) time into operas that have lasted for over a century.